Should we pay for the knowledge “protected” by copyright laws?

In the growing conflict between readers and authors, it is necessary to think of this question: should we pay for the knowledge “protected” by digital copyright laws?

My argumentattive essay in VG100 Academic Writing class.*

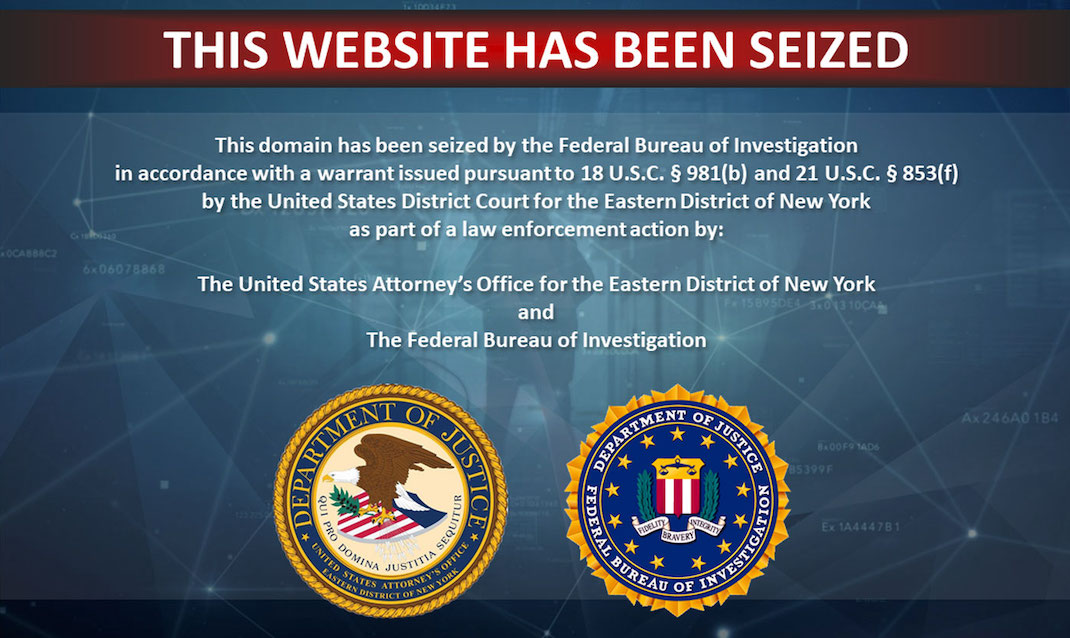

There has been a long and heated discussion about knowledge accessibility and copyright laws since the prevalence of digital resources as well as the legislation of digital copyright acts. Recently, with the shutdown of Z-Library, the biggest e-book and digital resource sharing website, the disputation between readers and authors, as well as copyright holders, has become a focus again. Readers, especially students, are mourning for the disappearance of free textbooks and academic papers, while authors and publishers are celebrating the “victory of law and order”. In the growing conflict between readers and authors, it is necessary to think of this question: should we pay for the knowledge “protected” by digital copyright laws?

In terms of academic sharing, the current copyright law or intellectual property law has been overused to some extent, which therefore reduces knowledge accessibility and causes inequality of individual’s right to reach knowledge.

Copyright laws

Copyright laws are laws that protect the rights of copyright owners, which has a similar function of intellectual property (IP) laws in terms of knowledge and academia protection. One of the most famous digital copyright laws can be Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), which was passed in 1988, aiming to punish digital piracy behaviors, so that the copyright owners can use technological protection measures (TPMs) to “protect their copyright works from unauthorized copying and unauthorized access to the works.” (Tana and Mwim, 2) According to Livia, With the worldwide tendency to “knowledge economy” (Livia, 548), there’s no doubt that copyright laws like DMCA, which encourage innovation of knowledge by requiring payment for the use of knowledge and therefore provides a possible return on investment, follow economic principles, and thus have obvious benefits on free market society. In addition, the copyright laws and intellectual property laws reinforce the punishment on academic misconducts, creating a better academic environment.

"Students don’t have that kind of money "

"Textbooks can cost up to $300 per course. Students don’t have that kind of money"

Washington Post, Marena Herron

However, the overuse of such laws, which leads to the violation of the rights of authors and readers, cannot be neglected. As copyright laws give rights of using technological protection measures to copyright owners, copyright owners may use their privilege to set high thresholds for both authors and readers. For example, CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure), the biggest digital academic database in China, with the protection of intellectual laws, is able to purchase copyright of authors in low price and ask readers and universities to pay for the contents by implementing technological protection. In such case, the copyright owners may not be the original authors and the “right of authors” is not protected. Furthermore, readers, or universities have to pay a lot for copyrights to get knowledge and resources. Due to the high payment, many readers and students are unable to access to the knowledge on CNKI. Therefore the “right of readers” is not protected either as monopoly and unfairness is caused. Examples as CNKI have proved that “the unregulated implementation of technological protection measures enables content providers to obtain protections the law does not afford.” (Lydia, 11) The law itself, has shortcomings which make the practice far from its original expectation. As mentioned in Calandrillo and Davidson’s article, the courts haven’t yet clarified or recognized fair use as a way to defend against violation of copyright laws. Therefore, it is not surprising that so many students turn to e-book websites like Z-Library mentioned at beginning to get text books or academic resources. These various cases have shown that it’s possible that only the copyright owners get benefits, and that the copyright law cannot protect the rights of authors and readers.

Monopoly of knowledge, a debate

“It is not possible for power to be exercised without knowledge; it is impossible for knowledge not to engender power.” (Foucault, 1980, p.52)

Besides overuse issues, the relationship between copyright laws and knowledge is also worth reconsidering because they can create a power imbalance.

Through the restrictions and payment requirements, copyright laws can give those who own knowledge a significant advantage over those who do not, which can allow the holders of knowledge to protect their own interests by excluding others from accessing it. As a result, these laws may serve to maintain the power of privileged groups and benefit only those who has already possessed knowledge. As Livia pointed out in her article, copyright laws often empower copyright owners, who are often not the original authors, and can hinder the accessibility of knowledge, stifling competition. In addition to these negative effects, copyright laws and intellectual property laws also have more subtle implications. They can influence the way knowledge is produced and shared, and can shape the way we think about the value of knowledge and the rights of creators. As such, it is important to carefully examine the implicit implications of these laws.

The monopoly of knowledge is no doubt not beneficial to the creation of knowledge and impedes the possibility of development of knowledge. The process of creating new knowledge demands for existing knowledge. However, when existing knowledge is “protected” by copyright laws and one is not able to access knowledge as he/she cannot afford the high price, how can he/she create new knowledge that can benefit the whole society? Is it fair to exclude those students who are eager to learn knowledge in developing countries from getting knowledge just because they cannot pay for the price of intellectual property? Knowledge should be accessible for everyone as knowledge is the ingenuity of the whole human being. Knowledge shouldn’t be only held by those who has power and wealth. Everyone has the right to learn and get knowledge.

It is no denying that monopoly of knowledge led by copyright laws has its meaning of existence. According to Clarence Ling’s article, without monopoly of knowledge, although everyone can have free and unrestricted access to work, the presence of direct devotion can decline, which lead to the decrease of the quality of the knowledge created. It is impossible and too idealistic to completely eliminate monopoly of knowledge and abolish copyright laws. However, the practice of such laws should be regulated and reconsidered to ensure a fair environment. It is suggested, like what is said in Pistorius and Mwim’s article, that “copyright laws should be adapted in accordance with their economic and social realities” (Pistorius and Mwim, 6). In addition, the future direction of copyright laws can be focused on reducing the overuse of monopoly and keeping a well balance between the benefits of authors, readers and copyright owners.

The end of law

While these laws can have positive effects on economic development and knowledge innovation, they can also create a monopoly on knowledge and restrict access to it. As John Locke famously wrote, "The end of law is not to abolish or restrain, but to preserve and enlarge freedom." (Locke, 1948) In the context of copyright laws and intellectual property laws, this means striking a balance between protecting the rights of creators and ensuring that knowledge is accessible to all. We should support creators by paying for the knowledge they produce, but not to the extent that it becomes prohibitively expensive for others to access. We can pay for knowledge, but not that much.

Calandrillo, Steve P., and Ewa M. Davidson. “The Dangers of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act: Much Ado About Nothing?” William & Mary Law Review, vol. 50, no. 2, Nov. 2008, pp. 349–415. EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=35776907&site=ehost-live.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-79, (Ed. Colin Gordon). New York: Pantheon.

Javaid, Maham. “The FBI Closed the Book on Z-Library, and Readers and Authors Clashed.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 17 Nov. 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2022/11/17/fbi-takeover-zlibrary-booktok-impacted/.

Ling, Clarence. “The Future of Copyright: Can We Do Away with Monopoly? Indicators from Libre Licensing.” ELaw: Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law, vol. 18, no. 2, July 2011, pp. 47–60. EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=77572532&site=ehost-live.

Livia Ilie, et al. “Intellectual Property Rights: An Economic Approach.” Procedia Economics and Finance, Elsevier, 17 Dec. 2014, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212567114008375.

Locke, John, 1632-1704. The Second Treatise of Civil Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration. Oxford :B. Blackwell, 1948.

Loren, Lydia Pallas. “Technological Protections in Copyright Law: Is More Legal Protection Needed?” International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, vol. 16, no. 2, 2002, pp. 133–148., https://doi.org/10.1080/1360086022000003964.

Pistorius, T. and Mwim, O.S. (2019) “The impact of digital copyright law and policy on access to knowledge and learning,” Reading & Writing, 10(1)., https://doi.org/10.4102/rw.v10i1.196.